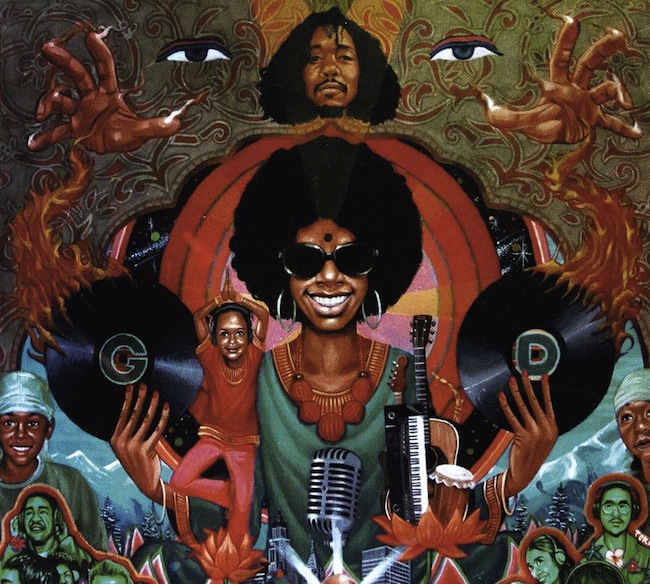

Georgia Anne Muldrow And Dudley Perkins Speak On The Funk, Black Power And Spirituality

After a heavy string of releases beginning in 2006 with her debut Worthnothings, Georgia Anne Muldrow eventually signed with the California based label, Stones Throw. Her husband, label mate and artistic partner Dudley Perkins (a.k.a. Declaime and former Madlib collaborator), both left the label in 2009 and went on to release music via Mello Music Group. Most recently the couple ventured off on their own in the creation of record label SomeOthaShip, a fitting title for their new music. Together, the pair released an initial full-length collaboration in 2007 with The Message Uni Versa under the collective name G&D. While they have followed up with other side projects and one-off collaborations (Georgia produced the entirety of Declaime’s 2011 LP Self Study and then linked up with Madlib for her own solo record Seeds the following year), the duo finally returned under the G&D moniker this past May with The Lighthouse.

In many ways, The Lighthouse airs out the couple’s most recognizable signatures: Georgia’s incessantly funky production, her meandering vocals, Dudley’s almost awkward rawness on the mic and more generally; their shared, somewhat oddball metaphysics. Our conversation launched almost immediately into Dudley explaining music’s inherently spiritual role (it’s “a nutrient”) and its recent fall from grace in the mainstream. In their music and in conversation, it’s easy to pinpoint some of the couple’s more out there musings, but in either case there’s an undeniable sense of understanding and passion about their work and life in general.

Can you explain your take on the function of music?

Dudley: Music is a very powerful tool, vibrations. Our bodies sort of function on a vibratory level, you know. Music rides on air, it’s something you can’t see. The divine things, the things you can’t see are very vital to human life. And music actually rides on these vibrations, on air, so it actually makes it a nutrient. It can actually tune you in or tune you out. We know the cats in the military [with their bombs], the murderers, the hired killers, when they go kill these kids and stuff like that, they actually listen to music to hype themselves up, you know? Or before people go do boxing or go do sports or other activities, there’s like a theme music popping off.

So I think, we’re just trying to play a part in the higher vibratory theme music, through all this bull-crap that’s going on in music. A lot of our brothers and sisters that are asleep through this music, a lot of the people that put them to sleep are [musicians] ‘cause they’re awarded for ignorance so they keep doing what they’re doing. But a lot of youth are waking up now, they’re not going to follow their fathers, uncles and mothers and their aunties and stuff down that road of dark music, music that has no place on earth.

Where do you see the Black Power movement in 2013, particularly within the context of music and musicians?

Georgia: For me, I feel like when a mother, a Black mother, carries a child in their womb, that’s Black power, you know? Black power is prevalent within every human life, but it’s just us in the societal construct who would be identified as Black, because we’re all of African ancestry, it’s a proven fact. It’s just basically, how Dudley was saying, you can Google a website that’s for elementary school students about African culture, you can go into a library and they’ll say “what is the instrument that comes to mind when you think of Africa?” The first instrument that comes to mind when you think of Africa is what?

The drums.

“...it’s an energetic thing, if I’m in a conversation with somebody I’m not just gonna be cussin’ them out and then expecting them to love me, you know? So why would you cuss somebody out on tape and tell them that they’re broke and I’m rich?”

Georgia: The drums right. Even a fool could recognize that that’s the heartbeat of our cultural expression. Then, let’s use that same tool that reached everybody, use it in the way that it was intended when it first got revealed to this planet. Because they had drums that could bring the rain, drums that could heal the sick people, drums that bring young boys into manhood and young girls into womanhood. We don’t have that in a prevalent level culturally in this country. And this is throughout the diaspora, there’s a lot of folks that go without these rites of passages [like] “now you are a man, now you are a woman, these are your responsibilities, these are your gifts.” We don’t have that, a lot of that was taken away, the drum was taken away We’re just a continuation of that metaphor really, it’s an energetic thing, if I’m in a conversation with somebody I’m not just gonna be cussin’ them out and then expecting them to love me, you know? So why would you cuss somebody out on tape and tell them that they’re broke and I’m rich?

The government talks to us from the TV, I don’t want to be like them. I don’t want to be like Obama. I definitely don’t wanna be just a source of entertainment when people are hurting, laughing is good but it’s better if someone can feel like a true healing from the inside instead of just a shallow laughter that distracts them from the problem. I rather if somebody is gonna laugh at what we’re doing it’s like an “aha” laugh, like “I’m finding it, I get it.” I’m not here just to be that entertainment and be that Betty Boop or that minstrel show kind of thing ‘cause we don’t think about those things in our daily conversations with people we love. Our conversations with people we love are about what tools do we have that we can further liberate the minds of our people, the hearts of our people, the physical bodies of our people, that’s our daily conversations so naturally it’s going to bleed into the music.

One of the things I was actually going to ask you about was about African cultural continuity and rhythmic continuity in particular, you already kind of answered my question.

Georgia: It’s really deep because Black folks is more African than they give themselves credit for, especially here, a lot of people really hang tight onto the “I’m African-American” and they really hang tight onto that. You’re just African, you’re living in this place but you are an African person, you know? I think one of the gifts of the diaspora is that we are not holding onto a nationality, we’re holding onto our genetic codes, our genetic memories and things that are within us that are very internal and I think that’s a beautiful thing. I think that’s very powerful. That’s why it’s been looked [on] with a lot of disdain and there’s been a lot of pain caused on people who claim that.

“You can say Jamaican pride all day, Panamanian pride, Ghanaian pride and everybody will love it and even the White folks will eat it up. But when you say Black pride and you say Black power and you say Black music, a lot of folks shy away from that because it’s intimidating.”

You can say Jamaican pride all day, Panamanian pride, Ghanaian pride and everybody will love it and even the White folks will eat it up. But when you say Black pride and you say Black power and you say Black music, a lot of folks shy away from that because it’s intimidating I think out of feelings of guilt that people have. When people want to put our struggle on the back burner and just look at countries and different things people do in the name of diversity, and when there’s something that unifying it puts people in fear because a lot of us have been breastfed on that colonial agenda and we don’t even know what it is. A lot of folks can’t even identify it within themselves but that’s the reason why people turn their nose up when you say “Blackness gives me power.”

We got the words going but at the same time it’s a vibrational thing, so even if somebody’s turning up their nose to a song like that, the vibrations is still going in there like medicine through their cells, through their eardrums, gotta process the music and it’s gonna leave some residue of some medicine in their brains. And that’s what we’re getting to ‘cause we’re living in a day and age when there’s a complete inundation of just jiveness, just straight up [shallowness]—either people that’s arguing on reality TV, causing destruction, chaos.

“The basis of Black power is to understand who we are, what it is that we have, the things that make us unique, the things that make us strong. So that we can go further without fear, because fear is based in lack, fear means that you think you lack the strength to handle a situation.”

The basis of Black power is to understand who we are, what it is that we have, the things that make us unique, the things that make us strong. So that we can go further without fear, because fear is based in lack, fear means that you think you lack the strength to handle a situation. When we go through life with a lower percentage of fear you’re more powerful, you know what I mean? And that’s really our aim, just to get people less afraid of themselves and to loving themselves and appreciate who they are.

It’s a spiritual battle, balancing your spirit in this society in this day and age is very real. If you have kids—you know we have kids—you see it clear and presently, the danger that they’re in. This is the way we pray, this is the way we meditate, this is the way we can recharge, just to make this music. And it’s a blessing that people like you call us asking us you know what’s behind this. Those are the side-effects, people embracing the music and buying the records.

So Georgia at some point you said “everything you do is gonna be Funky,” where does Funk fit in or how does it bring it all together?

Dudley: Well all music is Funk. I don’t know about Celtic music.

Georgia: Celtic got some Funk.

Dudley: They got a little bit of Funk?

Georgia: They probably got a little Funk in the Celtic. [Laughs]

Dudley: All music is Funk, it’s just when it’s done right it’s Funky.

Georgia: I always see the Funk as a manifestation of order within chaos. Because we live in a time that’s very disorderly and very offbeat, the adaptation of that environment into a new [way] of order. For me, when James Brown came with that whole philosophy of the one, of everything being on the one. You hear a song like “Make it Funky,” it’s a bad song but at the same time you hear a very militant vibe because everybody is in step with one another. And it’s like that’s the funk. Funk is very deliberate. It’s like this order that can’t be shook within any environment.

I was thinking about it, as a fan of Funk music but also just coming into this conversation that Funk isn’t just an aesthetic designation, there’s some energetic aspect to it as well.

Georgia: Absolutely. Yeah in anthropology you look, the roots of the word “funk” go very deep depending on where you go on the continent of Africa. It all comes back to Africa, you know. In Kikongo funk means to let loose spirit.

Oh wow I didn’t know that.

Georgia: Yeah and then if you go into the Wolof language “funk” means respect, to respect. If somebody has the funk on them they are respected. Another expression of funk is, you know, if you have exerted effort and you are sweating like literally to the funkiness, you have exerted that effort and work to the point that the funk is on you, and it’s merit.

“Also, when you disrespect the Funk, that’s not Funk...you can’t disrespect your ancestors, the women in your life, women on Earth, you can’t disrespect your people, you can’t use it for vanity, you have to use it to heal or to create that Funk...”

Dudley: Also, when you disrespect the Funk, that’s not Funk. It actually takes away steps from you, a few notes you’ll lose when you disrespect the Funk. That’s like disrespecting what people call God and stuff like that. You can’t disrespect your ancestors, the women in your life, women on Earth, you can’t disrespect your people, you can’t use it for vanity, you have to use it to heal or to create that Funk that Georgia said at the end of dancing and stuff like that. True Funk will have you dancing.

Georgia: Yes.

Dudley: But they got it twisted. They trying to funk with the Funk.

Georgia: It’s just like how you see beautiful movements like the Black Liberation Army, the Black Panthers and you can go further back to organizations like the Mau Mau and the Chimurenga, you know, these kinds of things. There was always some kind of agent there that tried to be an opposing force to that movement that was camouflaged in the rhetoric but the intention was completely different and you see the effects of that. And the Funk is the same thing, the cats that knowingly abuse [it] and choose to put the words of negativity and disunity and chaos into the Funk, those are people that me and Dudley consider as jive, completely part and parcel with whatever you want to call it, COINTELPRO, Patriot Act, you know, colonialism. Trying to get people’s mind to think in lack.

Alright last question, Georgia I read something where you said “you need to chart some spiritual territory in the realm of computer music,” we’ve talked about this on the site before that music made on the computer can incite some kneejerk response that’s it’s not real or organic, so what did you mean when you said that?

Georgia: That’s a very good question because it’s a dialogue I have with my folks all the time. And we stay in dialogue about that and the whole analogue versus digital and the kind of mind game that people try to play on folk that it’s different when there ain’t really no difference. It’s your mind, it’s in your mind.

You gonna hear me repeating myself a lot because at the end of the day it goes from feelings that you have, feelings of empowerment versus feelings of lack. So when you’re on the computer and you got these feelings of lack going on, you know like you want to quantize every single little thing, quantizing means like the beats your programming are corrected by the computer, the computer is thinking for you. You’re not trying to customize no sounds [or] find your voice, you know? So that the computer can be your tool instead of you being the tool of the computer. Anything that you’re doing, whether you’re a writer, a painter, in any aspect of the world or just as a person, you need to find your unique voice because we’re all made uniquely.

“For me I don’t see it as no different thing, I’ll get on the drum set but I can make the computer sound like the drum set I can’t afford. For me I like computers because they free me of a lot of limits, and the only limit is what’s coming through me.”

For me I don’t see it as no different thing, I’ll get on the drum set but I can make the computer sound like the drum set I can’t afford. For me I like computers because they free me of a lot of limits, and the only limit is what’s coming through me. The environment that I’m very privileged and honored to have is with the ancestral rhythm. And they using me to do this music so even if I was on a rubber band on a corner, they’re gonna use me to do whatever I gotta do.

That’s my whole thing, I feel like a lot of the dance music is a beautiful thing because it got this tribal sound but I think at the same time it would do good for folks to really do their research on the music of the world instead of just kind of assume a one dimensional aspect of tribal music.

You talk about binary code, that ain’t nothing but rhythm. That’s a hand [on] and a hand off of a drum, that’s the way I see it. Even furthermore, a lot of people have made correlations to Nigerian or West African divination having a lot to do with the creation of binary code. We have this diviners that have either shells or nuts and they cut them in half, you know, and depending on which way up or down it’s a whole program, it’s a whole story and how they can go on to correct the things in their life. So this computer thing is older than just like a CPU. When I look more into what computers are and what they’re capable of it’s right in step with throwing shells on the diviner’s board, it’s the same thing. It’s a beautiful honor to be a part of something that’s so old and not going away and will never die which is music, it’s an honor for us to be a part of that because it ain’t going nowhere.

Words by Jay Balfour

Originally from Western Massachusetts, Jay Balfour is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer. In addition to Project Inkblot, Jay also writes for HipHopDX, OkayAfrica, and the print publication, Applause Africa. A graduate of Temple University’s Philosophy and African-American Studies departments, Jay focuses on Hip Hop, Soul, Funk, Jazz and Latin records and the stories behind their creation. Questions or comments about this interview? Hit Jay up via Twitter.